The patterns seen in first-pass regressions are more interesting. By contrast, in ungrammatical conditions, agreement conditions show a clear indication of the predicted facilitation, whereas reflexives do not show any interference. The posterior distribution of the dependency × interference interaction has a mean of −2.4%, and a credible interval of [−4.7, 0.0]%.

Figure 9 shows the interference effects in first-pass regressions estimated from the replication data together with the ones obtained from the original data of Dillon et al. . Quantitative predictions of the cue-based retrieval model are not shown because there is no obvious linking function that quantitatively maps retrieval time in cue-based retrieval theory to first-pass regressions. A comparison of the quantitative model predictions with the replication estimates shows that the model's predictions for ungrammatical sentences are consistent with the observed estimates in the replication data. Thus, the mean effects in the replication data are consistent with the view that tree-configurational and non-configurational cues have equal weight. Interestingly, our findings in this replication attempt conflict with those of our recent meta-analysis, where we found facilitatory interference only in ungrammatical configurations of subject-verb agreement, but not in reflexives (Jäger et al., 2017).

Since there are several statistical and methodological issues (e.g., low power, and confounds in the experimental materials), we consider the contribution of the meta-analysis to be limited to summarizing the published literature in a quantitative manner. Interference effects in grammatical and ungrammatical conditions . The figure shows the posterior means together with 95% credible intervals of the interference effects in total fixation times.

These estimates were obtained from the Bayesian analysis of the original data of Dillon et al. , and from our replication data. Separate effect estimates for each dependency type as well as the overall effect obtained when collapsing over dependencies are presented. The left-most line of each plot shows the range of predictions of the Lewis and Vasishth ACT-R cue-based retrieval model (see Section Deriving quantitative predictions from the Lewis and Vasishth model for details).

The results of our investigations of the total fixation time data are summarized in Figure 10, which also shows the estimates from the data in the original study by Dillon and colleagues. The quantitative predictions of the Lewis and Vasishth ACT-R cue-based retrieval model are also shown in the figure. These predictions are generated with the assumption that syntactic cues do not have a privileged position when resolving dependencies of either type. As in the total fixation time analysis of the original data, total fixation time in the replication data do not show any indication for a difference between the interference profiles of the two dependency types. Indeed, we find almost identical estimates for the speedup in ungrammatical sentences involving subject-verb agreement and reflexive dependencies. This is not consistent with the idea, suggested by Dillon and colleagues, that there are contrasting interference profiles for agreement vs. reflexives.

Furthermore, the estimated facilitation in the agreement conditions is much smaller for our larger-sample replication attempt than the estimate obtained from the original data. Type M errors can occur when statistical power is low (for a discussion of Type M errors in psycholinguistics, see Vasishth, Mertzen, et al. 2018). Analysis of first-pass regressions out of the critical region. The figure shows the posterior means together with 95% credible intervals of the interference effects in the percentage of first-pass regressions. Quantitative predictions of the cue-based retrieval model are not shown alongside the regression probabilities because there is no obvious linking function that quantitatively maps retrieval time in cue-based retrieval theory to first-pass regressions. Knowledge of the S-V agreement rule is thus considered to facilitate successful sentence comprehension.

The present study therefore examined how effects of perceptual salience due to utterance position and type of agreement violation may modulate the neural responses to S-V agreement violations during on-line speech comprehension. The findings contribute to our understanding of the types of information that influence on-line sentence comprehension, and have implications for study design. Possible outcomes when interpreting the empirical data against predictions of the Lewis and Vasishth cue-based retrieval model. A-F represent the 95% credible intervals of hypothetical posterior distributions of the interference effects as estimated from the data. Outcomes A and B falsify the model, outcomes C and D are equivocal outcomes, and E would be strong support for the model. Outcome F is uninformative and can only occur when the data does not have sufficient precision given the range of model predictions.

The figure is adapted from Spiegelhalter et al. (1994, p. 369). The verbs were inserted into carrier sentences that were composed of monosyllabic words, thereby controlling for utterance length and processing load. The carrier sentences had a singular vs. plural subject to enable manipulation of type of agreement violation (verb-form without −S/errors of omission vs. verb-form with −S/errors of commission). The verbs appeared in the middle vs. end of the carrier sentence to create the utterance-medial vs. utterance-final conditions, respectively . In the utterance-medial position, the verb was always followed by a preposition with a vowel onset to avoid masking of the morpheme in the preceding verb. All sentence stimuli were accompanied by cartoon pictures that were designed by a professional cartoonist .

The drawings had a constant level of visual complexity to avoid distracting details. The purpose of the pictures was to sustain participants' attention, and keep their eyes focused on the computer display to minimize head movement . Recall that Dillon et al. concluded that the processing of the different syntactic dependencies differs with respect to whether all available retrieval cues are weighted equally and are used for retrieval, or whether structural cues are used exclusively. This claim is based on their Experiment 1, which directly compared interference effects in subject-verb agreement and in reflexives.

The main finding was that in total fixation times, facilitatory interference is seen only in ungrammatical subject-verb agreement sentences but not in ungrammatical reflexive conditions. The histograms show the distributions of the model's posterior predicted interference effects in grammatical vs. ungrammatical conditions, for agreement and reflexive conditions. We used the total fixation time data from Dillon et al., 2013 to estimate the latency factor parameter from the LV05 model. See the accompanying MethodsX article for details on how the latency factor parameter was estimated .

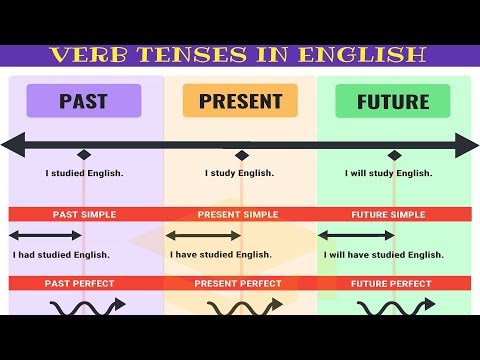

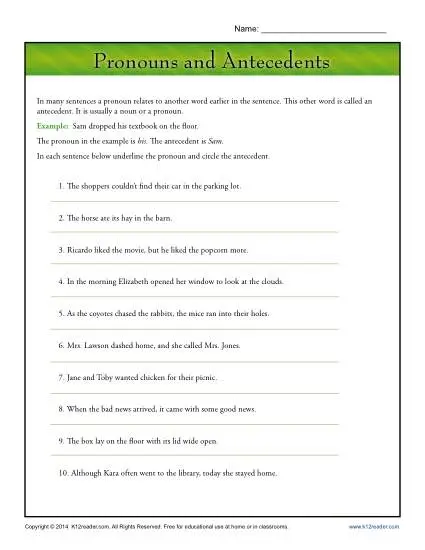

Students' topic-based writings were examined by the author. The findings suggest that misuse of tense and verb form was the most frequent error in Chinese students' writings. Others include those in spelling, use of particular words and phrases, Chinese-English expression, singular and plural form of nouns, parts of speech, non-finite verbs, run-on sentences, pronouns and so on. Teachers should pay due attention to all of the errors, especially those frequent ones, and try to find out what leads to those errors, thus, they may give their students effective grammar and writing instructions to help them with English learning. © 2015 Canadian Center of Science and Education, All right reserved.

The correct sentence is Nearly one in four people worldwide is Muslim. The subject of the sentence is one, which is singular and takes a singular verb. The rule you are writing about only applies to collective nouns. The word one is not a collective noun, it is a singular noun.

In the sentence A family of ducks were resting on the grass, the subject of the sentence is family, which is a collective noun. In this case, the writer may decide whether to use a singular or plural verb, depending on whether he thinks of the "family" as a unit or as individual beings within that unit. We begin by reporting the results of the cluster-based permutation tests, which contrasted the grand average ERP waveforms of the grammatical condition with those of ungrammatical condition . Second, we were interested in comparing cue-based retrieval theory's predictions with the total fixation time data in Dillon et al. 's original study and in our replication attempt. We were specifically interested in comparing the model predictions to the observed interference patterns in grammatical and ungrammatical conditions. This study does not allow us to resolve the debate on the processes underlying sentence comprehension.

However, it is worth considering how our findings might be incorporated into existing theoretical accounts for the functional interpretation of the LAN/P600 components. We argued that these inconsistencies may in part be due to confounding influence the ERP effects during the LAN/AN time window. Importantly, our analysis collapsing across all conditions revealed both AN and P600 effects indicating that listeners detected the morphosyntactic violation and engaged in syntactic re-analysis.

The comparisons we conditions represents what Steinhauer and Drury have referred to as a "balanced" design with the same noun and verb forms occurring equally across conditions such that all confounding factors average out. Due to concerns about the statistical power of Dillon et al. 's Experiment 1, we carried out a direct replication attempt with a larger participant sample. The relatively low power of the Dillon et al. study can be established by a prospective power analysis, which is discussed in detail in Appendix A. Here, we briefly summarize the methodology adopted for the power analysis. These posterior predictive distributions were computed using the Dillon et al. data and the simplified Lewis and Vasishth 2005 model as implemented by Engelmann et al. . For agreement, the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile were −48, −39, and −32 ms; and for reflexives, they were −32, −23, and −14 ms. Figure 7 compares the range of effect sizes predicted by the LV05 cue-based retrieval model with the empirical estimates obtained from Dillon et al. 's Experiment 1 total fixation time data.

The figure shows the estimated interference effects observed in total fixation times within each level of grammaticality for the two dependency types separately (i.e., the estimates obtained from Model 2), and collapsed over the two dependency types . Another unique situation that affects subject-verb agreement involves the use of collective nouns.Collective nouns are singular nouns that refer to groups of people. On the SAT, these nouns, if used in the singular form, should be used with singular verbs.Examples of collective nouns include team, band, company, and committee. Grand average ERP waveforms for grammatical and ungrammatical conditions across positions and type of agreement violation at the F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4 electrodes and the topographic maps of the significant ERP effects.

The first row of the figure shows the anterior electrodes while the second row shows central electrodes and the third row shows the posterior electrodes. The ERPs are time-locked to the offset of the verb-stem and positivity is plotted upwards. The topographic maps show brain voltage distributions for the negative and positive clusters. These maps were obtained by interpolation from 64 electrodes and were computed by subtracting the grand averages of grammatical from the ungrammatical conditions. Electrodes in the significant clusters are highlighted with a black circle and the F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4 electrodes in the significant clusters are highlighted with a white circle.

Time-windows for significant clusters is highlighted in gray over the waveforms. Returning to the confirmatory analysis involving total fixation times, we can conclude the following. The total fixation times show nearly identical facilitatory interference effects in both dependency types, suggesting a similar retrieval mechanism.

Our conclusion that different dependencies might have a similar retrieval mechanism is also supported by a recent paper by Cunnings and Sturt , which found facilitatory interference effects in total fixation time in non-agreement subject-verb dependencies. Of course, larger-scale replication attempts should be made to replicate the findings that we report here; in that sense, our conclusions should be regarded as conditional on the effects replicating in future work. The credible intervals in both agreement and reflexives are very wide, leading us to conclude that these data are uninformative for a quantitative evaluation of the Lewis and Vasishth cue-based retrieval model. A higher-power study is necessary to adequately evaluate these predictions; for detailed discussion on power estimation see Cohen and Gelman and Carlin .

I also find the use of the plural form with collective nouns problematic. One of the examples given begs the question by the use of "their" as the prepositional pronoun. If "team" is taken as singular then the correct pronoun would be "it" giving "The team was happy with its presentations." This seems perfectly acceptable to me even though the prepositional noun "presentations" is plural. This would seem to contradict the claimed principle that the case rests on the plurality or not of the prepositional noun phrase. An important decision in conducting data analysis was how to pair ungrammatical sentences with corresponding grammatical sentences. For example, the ungrammatical sentence "The boys often cooks on the stove" could be paired with "The boys often cook on the stove," keeping the context consistent but changing the inflection on the verb.

However, in auditory studies, this entails that grammaticality effects are confounded with differences in the acoustic content following the verb stem, in terms of both the presence/absence of the −s and the timing of the subsequent word. This in turn means that "grammaticality" effects on ERPs may arise even when participants are insensitive to the grammatical violation. We therefore chose instead to manipulate the context whilst keeping the verb inflection constant by comparing the grammatical vs. ungrammatical verbs across the singular and plural conditions. (e.g., The boy often cooks on the stove vs. The boys often cooks on the stove).

This removes any potential acoustic confound following the verb. However, Friederici's model of sentence comprehension is not explicit on whether or how the nature of incoming syntactic and other types of information may modulate the LAN and P600 effects. As a result, the model has been challenged by studies which have observed these ERP effects to vary in their presence, latency, amplitude, and distribution as a function of the characteristics of the morphosyntactic elements in question. For example, some studies investigating agreement processing, in languages other than English, have reported an N400 effect instead of the typical LAN effect (e.g., Wicha et al., 2004). Others did not observe the LAN (e.g., Osterhout et al., 1994; Hagoort and Brown, 2000; Kaan et al., 2000; Kos et al., 2010).

On the other hand, while the P600 effect is often reported for agreement violations, some studies have not reported it (e.g., O'Rourke and Van Petten, 2011). This variable realization of the LAN and P600 effects has resulted in some scholars questioning the modular functional interpretation of these ERP components (for discussion, see Kaan and Swaab, 2002; Bornkessel-Schlesewsky et al., 2015; Tanner, 2015). In the following paragraphs, we take a closer look at previous ERP studies that have investigated S-V agreement processing involving inflectional violations, as summarized in Table 1. Given that both errors of omission and commission result in S-V agreement violations, we would expect listeners to be equally sensitive to the grammatical violation.

However, there are a number of reasons to assume that listeners might be more sensitive to errors of commission compared to errors of omission. One of the assumptions is that listeners often perceive speech sounds that they expect to hear even when they are physically absent from the stimuli, that is, phoneme restoration . This may make omission errors more difficult to detect than commission errors in which an unexpected morpheme is inserted into the speech. Another related assumption is that with auditory presentation, the perception and identification of the morpheme may be dependent on its physical characteristics, which may in turn affect the detection of agreement violations. Thus, the mere presence of the superfluous −s morpheme in the errors of commission makes the violation more overt compared to errors of omission. Listeners might therefore be more sensitive to the overt error.

Our second research goal was to conduct a quantitative evaluation of the predictions of cue-based retrieval theory. Here, the relevant comparisons are the interference effects within grammatical and ungrammatical conditions of Model 1. None of the other fixed effects are of theoretical interest to our research goals and are only included to reflect the factorial design of the experiment.

The use of singular vs. plural verbs with collective nouns is a matter of writer's intent (see Rule 9 of Subject-Verb Agreement). With portion words we are guided by the noun after of (see Rule 8 of Subject-Verb Agreement). The use of the plural pronoun their in Pop Quiz question No. 2 does force the collective noun team to be considered as plural. However, we feel that this question can be more instructive revised to allow our readers to interpret its meaning, which we have done.

Besides the latency differences occurring between different modes of presentation, the scalp distribution and the size of the P600 component reported in previous studies also differ as a function of syntactic complexity. The differences observed in the scalp distribution and sizes of the components are assumed to reflect the degree to which the brain is engaged in syntactic reanalysis (e.g., Osterhout et al., 2004). These findings show that ERPs are ideal for identifying factors that modulate the processing of S-V agreement violations during sentence comprehension. However, they also indicate that different methodological aspects of the experiment influence the realization and interpretation of the ERP components.

All interference effects were coded such that a positive coefficient means inhibitory interference, i.e., a slowdown in reading times in the interference conditions. A positive coefficient for the main effect of grammaticality means that the ungrammatical conditions are read more slowly and a positive coefficient for the effect of dependency means that agreement conditions take longer to read than reflexive conditions. All contrasts were coded as ±0.5, such that the estimated model parameters would reflect the predicted effect, i.e., the difference between the relevant condition means (Schad, Hohenstein, Vasishth, & Kliegl, 2019). Fractions and percentages can either be singular or plural depending on the object of the preposition following. In this case people is the object of the preposition of.

If you are still confused, please see our post When to Add s to a Verb. Some collective nouns may take either a singular or a plural verb, depending on their use in the sentence. Collective nouns can be tricky because it is up to the author of the sentence to determine whether the noun is acting as a single unit, or whether the sentence indicates more individuality.

In your first example, "India has a team of players who are dedicated," the team of players are acting with individuality within the unit. In your sentence "A group of doctors is traveling to Haiti," the word group is a collective noun that is acting as a unit. Therefore, it is treated as a singular noun and uses the singular verb is. In view of this, either "Loss of life and serious injury in our skies are unacceptable" or "Loss of life and serious injury in our skies is unacceptable" is all right. I respectufully disagree with your use of the plural verb form when referring to "team or staff". I recently heard a national TV reporter use a plural verb when refering to a married COUPLE–she used it twice.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.