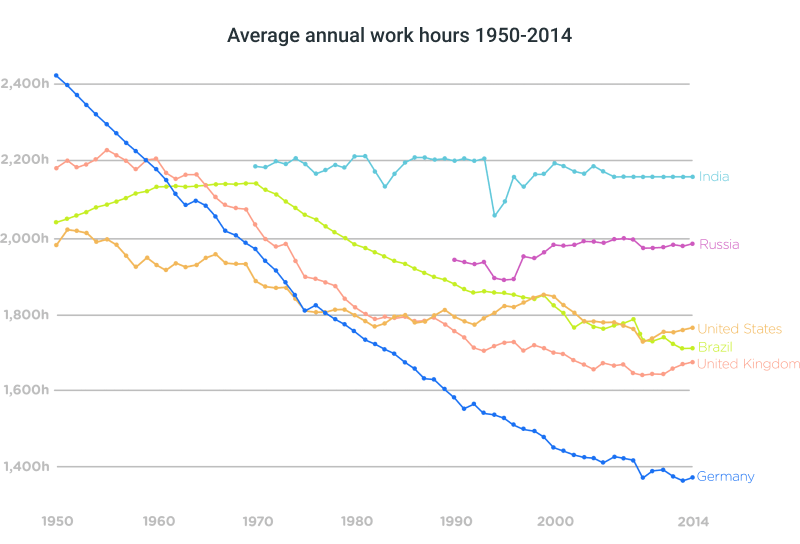

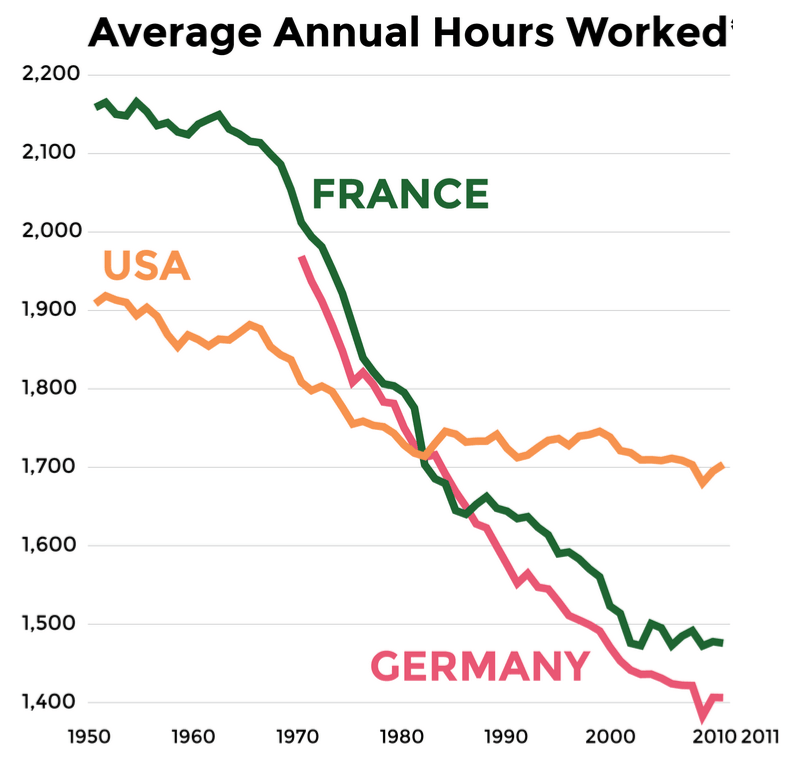

The chapter also provides an update on working time trends across OECD countries. It shows that usual weekly hours, and the incidence of paid overtime have remained relatively stable over recent decades. Taken together , parallel trends in average annual hours worked, average time spent on leisure, and hourly productivity suggest that productivity increases have not led to extra leisure time. One possible explanation for this is that workers faced with a decreasing labour share have opted for increases in hourly wages rather than reduction in hours worked.

In Germany, the April 2020 Working Hours Ordinance authorised an extension of daily working time up to 12 hours, while the weekly working time could be extended beyond 60 hours in exceptional cases. In Greece, between March and August 2020, employers who had exhausted the legally prescribed overtime ceilings of their workers, could use overtime without approval from the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs in the respect of maximum daily limits. In Israel, the Ministry of Labour introduced in March 2020 a temporary permission to work additional hours up to 67 hours a week but no longer than 90 extra hours a month. The permission also included the possibility to work up to 14 hours a day including overtime, up to 8 times a month.

In Norway and Sweden,75 national-level collective agreements gave room for more flexibility to actors at the local level regarding the extended use of overtime. Although standard hours agreed on at the sectoral level in Germany have not changed since the beginning of the century, some companies applying such agreements have increased standard hours. For some industries, collective bargaining agreements concluded at the industry level between trade unions and employers allow establishments, under certain conditions, to deviate from collectively agreed standards on pay and working time.

In the 2005 wave of the Institute for Employment Research's Establishment Panel, 13% of establishments had such agreements, and 52% of them made such changes, usually in standard hours . In the metalworking industry, for example, the collective agreement allows 13–18% of the workforce to deviate from the standard 35-hour week and to work between 35 and 40 hours. In addition, under certain conditions, up to 50% of employees could work up to 40 hours. The agreement also stipulates that jobs must not be cut as a consequence of increasing the quota above 18% and that hours beyond 35 hours will be paid, but without an overtime premium .

As for normal hours, procedural requirements and modalities vary across OECD countries. In Austria and Denmark, averaging of maximum weekly hours requires a collective agreement. In Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Norway and Portugal, the averaging of maximum weekly hours can be introduced pending employees' consent. In Hungary,25 the Netherlands, Slovenia or Sweden, maximum weekly hours can be averaged unilaterally by employers. Reducing standard hours in order to distribute a given amount of work over more employees has been a popular policy tool in several countries, in particular in the 1980s and 1990s. However, econometric evidence suggests that, at best, there were no positive employment effects, mainly because hourly wages were increased in order to leave monthly pay unchanged.

In the early 2000s, and bucking the trend, several firms in Germany increased standard hours. Theoretical studies show that several conditions must be met for an increase in standard hours to have positive employment effects. In the short term, when output is fixed, extensions in standard hours may even have detrimental effects on employment. In the long term, the outcome is more optimistic, and additional jobs may be created. However, the employment effects crucially depend on the response of hourly wages.

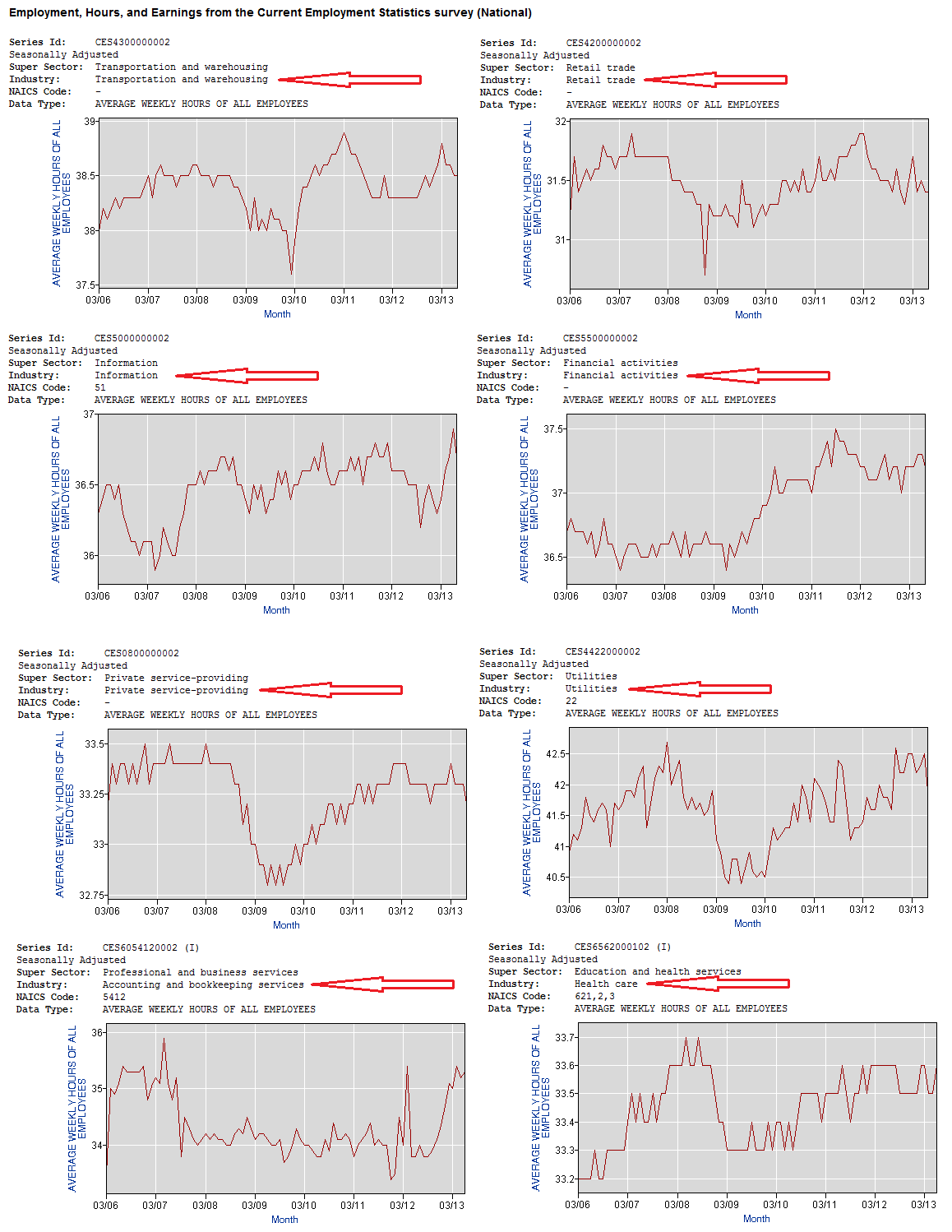

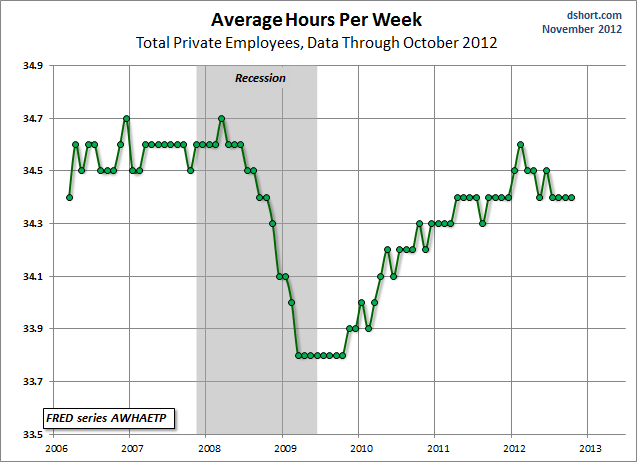

If hourly wages fall, keeping monthly income constant, employees who had been working before the increase in hours are clearly worse off , but employment is likely to rise. Irrespective of the quantitative effect of any employment increases, the reduction in labor costs should help to protect jobs in firms under competitive pressure. Looking at trends in usual weekly hours and weekly overtime illustrates how the usual week of the average full-time employee in the OECD has evolved in the last decades. However, it cannot be used to assess how the overall quantity of work per full-time employee changed over time, since the latter is also a function of the number of weeks worked , in addition to the usual amount of work per week. However, there are no sources allowing for a reliable comparison of days off taken across countries.

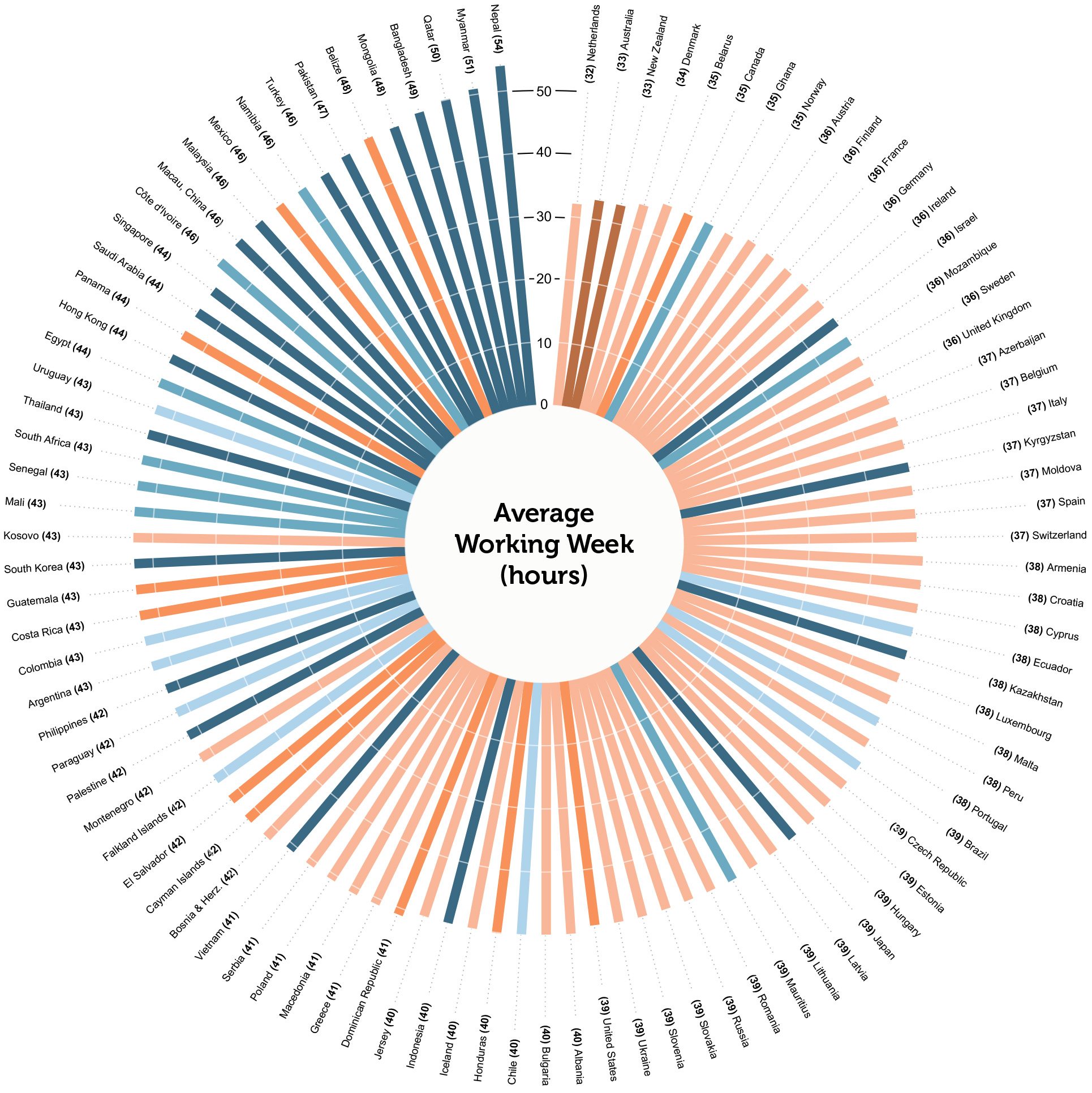

Mexican labour law states that employees working during the day can work 48 hours per week . Overtime is capped at 9 hours per week which must be paid at 100% of the normal wage. There is little regulation of rest periods and a minimum of 6 days paid annual leave after 1 year of service. In 2019, Mexico had the highest recorded average of 2137 annual working hours in the world. The Working time regulation is one of the oldest concerns of labour legislation in the world. Early, in the 19th century, it was recognized that working excessive hours posed a real danger to workers' health and their families.

The working hours limits has been effective since the first ILO Convention, the Hours of Work Convention, 1919 (No. 1), which stipulates the principle of the eight-hour day and 48-hour week for the manufacturing sector. The reduction of working hours was one of the original objectives of employment regulation. A number of instruments including international labour standards have been used to help implement this regulatory framework in countries. National legislation is a second instrument of working-time regulation, and collective agreements are a third. Whaples finds that among the most important city-level determinants of the workweek during this period were the availability of a pool of agricultural workers, the capital-labor ratio, horsepower per worker, and the amount of employment in large establishments.

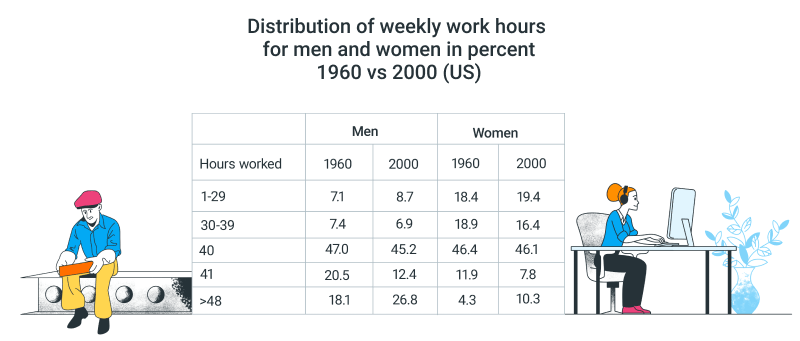

Eastern European immigrants worked significantly longer than others, as did people in industries whose output varied considerably from season to season. High unionization and strike levels reduced hours to a small degree. The average female employee worked about six and a half fewer hours per week in 1919 than did the average male employee. In city-level comparisons, state maximum hours laws appear to have had little affect on average work hours, once the influences of other factors have been taken into account. One possibility is that these laws were passed only after economic forces lowered the length of the workweek.

Hours In A Work Week By Country Overall, in cities where wages were one percent higher, hours were about -0.13 to -0.05 percent lower. Again, this suggests that during the era of declining hours, workers were willing to use higher wages to "buy" shorter hours. Historically employers and employees often agreed on very long workweeks because the economy was not very productive (by today's standards) and people had to work long hours to earn enough money to feed, clothe and house their families.

The long-term decline in the length of the workweek, in this view, has primarily been due to increased economic productivity, which has yielded higher wages for workers. Workers responded to this rise in potential income by "buying" more leisure time, as well as by buying more goods and services. In a recent survey, a sizeable majority of economic historians agreed with this view. Over eighty percent accepted the proposition that "the reduction in the length of the workweek in American manufacturing before the Great Depression was primarily due to economic growth and the increased wages it brought" .

For example, roughly two-thirds of economic historians surveyed rejected the proposition that the efforts of labor unions were the primary cause of the drop in work hours before the Great Depression. Here again, Figure 5.3 does not display a clear-cut relationship between the degree of variation allowed in the rules and the actual degree of variation in outcomes observed. The median amount of paid overtime for full-time employees tend to stay within the limits fixed in the law or in higher level collective agreements in most countries47 that give extensive possibility for the upper limit on overtime to vary.

Working time is a crucial variable shaping the labour market and its adaptability to shocks. It can affect key labour market outcomes, such as workers' well-being, productivity, wages and employment. Documenting how OECD countries regulate working time, and understanding how different regulatory settings shape working time outcomes is crucial for policy makers seeking to balance equity, efficiency and welfare considerations. This chapter offers a detailed review of regulations governing working hours, paid leave, and teleworking in OECD countries.

It discusses the role of collective bargaining in negotiating working hours or working time arrangements, and how OECD countries have adapted their working time regulation during the COVID-19 crisis. The chapter also provides an update on working time patterns and trends in time use across OECD countries and socio-demographic groups. It measures how differences across workers in working time outcomes have changed over time and driven inequalities in work-life balance. It seems plausible to look at firm−union bargaining models to explain the change in hourly wages accompanying an increase in standard hours , because the increases in standard hours in Germany often took place in large unionized firms.

However, the response of hourly wages under collective bargaining agreements is difficult to predict. Any response in monthly pay may also depend on the original level of working time. If original working time was low, monthly pay is less likely to increase very much (see for a formal model). Therefore, all else being equal, it might be easier to increase employment by increasing standard hours in countries where working time is comparatively low. It should also be kept in mind that the existence of minimum wages may rule out a drop in the hourly wages of workers on the lower part of the wage distribution following an increase in standard hours. Finally, it is an open question how hourly wages respond in the long term.

Compared to the European countries listed here, similar regulations apply to employees in federally regulated industries in Canada. There are industry and regional variations, but generally, employment law limits the workweek to a maximum of 48 hours, including overtime. Overtime is allowed and must be paid at a rate of 1.5 times the normal wage.

However, compared to its European counterparts, the average annual working hours in 2019 were higher at 1670 hours. The number of RTT days varies every year but is around 10 days annually. Another scenario is also possible, in which monthly wages and hours are jointly determined in long-term contractual agreements . In other words, market equilibrium may be thought of as reflecting the satisfaction of joint preferences across employers and individual workers with labor demand equal to labor supply at all hours worked .

To preserve a given package of hours and earnings, firms and individual workers respond to regulatory measures by adjusting the hourly wage rate and possibly overtime hours. Keeping the hourly wage and total hours constant would reduce earnings because a smaller fraction of workers will receive an overtime premium because a smaller fraction of hours is compensated with an overtime premium. Thus, to maintain the agreed earnings, hourly wages will be adjusted upward and the increase in standard hours will have no effect on total hours and employment. This scenario differs from the one described previously, in which the hourly wage falls to keep monthly earnings constant when total hours rise. The effects of overtime regulation in the US are found not to be fully consistent with either the labor demand model or with the fixed hours/average wage model . One criticism of the fixed hours/average wage model is that only a fraction of workers work overtime and for those who do not work overtime an increase in standard hours will inevitably change hours worked.

Many countries regulate the work week by law, such as stipulating minimum daily rest periods, annual holidays, and a maximum number of working hours per week. Working time may vary from person to person, often depending on economic conditions, location, culture, lifestyle choice, and the profitability of the individual's livelihood. For example, someone who is supporting children and paying a large mortgage might need to work more hours to meet basic costs of living than someone of the same earning power with lower housing costs.

In developed countries like the United Kingdom, some workers are part-time because they are unable to find full-time work, but many choose reduced work hours to care for children or other family; some choose it simply to increase leisure time. In Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Latvia, and the Slovak Republic, rules governing maximum weekly hours/overtime are likely to be mostly uniform. The upper limit is binding, but there is a limited possibility to use averaging mechanisms, only with the employee's consent or through a collective agreement.

In all these countries but Latvia and Denmark, there is a binding minimum compensation for overtime hours . As the length of the workweek gradually declined, political agitation for shorter hours seems to have waned for the next two decades. However, immediately after the Civil War reductions in the length of the workweek reemerged as an important issue for organized labor. Roediger argues that many of the new ideas about shorter hours grew out of the abolitionists' critique of slavery — that long hours, like slavery, stunted aggregate demand in the economy. The leading proponent of this idea, Ira Steward, argued that decreasing the length of the workweek would raise the standard of living of workers by raising their desired consumption levels as their leisure expanded, and by ending unemployment.

The hub of the newly launched movement was Boston and Grand Eight Hours Leagues sprang up around the country in 1865 and 1866. The leaders of the movement called the meeting of the first national organization to unite workers of different trades, the National Labor Union, which met in Baltimore in 1867. The passage of the state laws did foment action by workers — especially in Chicago where parades, a general strike, rioting and martial law ensued.

In only a few places did work hours fall after the passage of these laws. Many become disillusioned with the idea of using the government to promote shorter hours and by the late 1860s, efforts to push for a universal eight-hour day had been put on the back burner. The second block was dedicated to the regulation of the amount of hours worked . The third block examined the regulation of leave and public holidays. The fourth block looked at the regulation of the organisation of working time (e.g. unsocial hours and flexible working time arrangements).

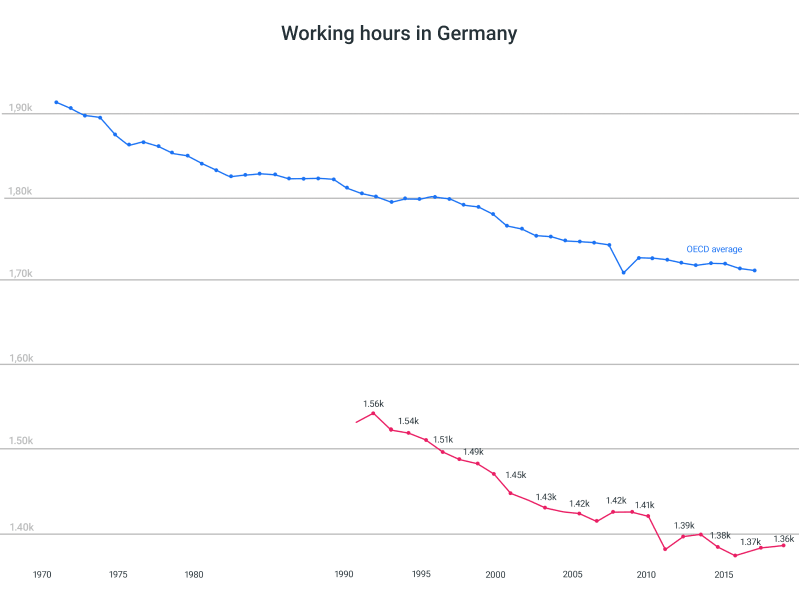

The fifth block collected information related to the existence of short-time work and more generally job retention schemes and how they have been adjusted as a response to the COVID-19 crisis . Finally, the sixth block focused on recent reforms of working time regulation. In Germany, the total volume of paid overtime hours was cut in half between 1991 and 2014, while unpaid work rose 16% and now exceeds the amount of paid overtime.

In 2014, employees worked on average 21.1 paid overtime hours and 27.8 unpaid overtime hours. Paid overtime constituted just 1.6% of all hours worked (Wanger et al., 2015). Still, the actual volume of 0.8 billion overtime hours is equivalent—assuming equal productivity—to about 550,000 employees working standard hours. According to data from the IAB Establishment Panel, in 2011, 21% of private establishments paid overtime, and 55% of their employees actually worked paid overtime; 19% of all employees in the private sector worked paid overtime.

The difference between collectively agreed standard hours per week and reported actual working hours is 2.7 hours, which is larger than in most other European countries . In the short term, when it is difficult to boost output, increasing standard hours is likely to have negative employment effects. Over a longer period, when output and capital can vary, positive employment effects are more probable if monthly pay remains unchanged. However, if hourly wages remain unchanged or decline, employees who had been working before the hours increase are worse off. Extending standard hours can also safeguard jobs in firms under competitive pressure.

It may be advisable to have flexible arrangements that allow establishments to deviate slightly from collective bargaining agreements on work time. Standard hours, a major component of total work hours, vary considerably across Europe. Many countries lowered their standard work hours during the 1980s and 1990s, attempting to boost employment by splitting up a fixed number of worker-hours among more workers.

Germany has seen a partial reversal of the trend as several companies increased their standard hours to reduce their labor costs in the early 2000s. The employment effect of increased standard hours depends on the time horizon examined, how wages respond, whether employees collected overtime pay before the change, and the productivity of hours worked, among other factors. For non-exempt employees, the Fair Labor Standards Act stipulates a standard 40 hour workweek in the US. Anything above is considered overtime and must be paid at a rate of 1.5 times the normal wage. However, there is no limit on the amount of overtime or hours of work per week and little regulation of annual leave and rest periods. The average annual working hours in the US were rather high at 1779 hours in 2019.

When employing remotely, you will need to be aware of the variation in working hours across your team so you can employ your remote talent compliantly. Though certain international standards prevail, different countries' working hours vary a lot. What's more, while labour laws set standards, the reality can still be quite different. For example, men tend to work longer hours in paid employment compared to women, particularly where maximum legal working hours are high. The amount of paid leave and public holidays also affects the total number of hours people work in a year. Beyond regular working hours, it is legal to demand up to 12 hours of overtime during the week, plus another 16 hours on weekends.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.